COLIC

An extremely common condition in horses.

Acting quickly is crucial!

Contact Us

(08) 9296 6666 (office hours & after-hours emergency)

admin@belvoirequinehospital.com.au

Lot 158 West Swan Rd, Belhus, WA 6069

Colic

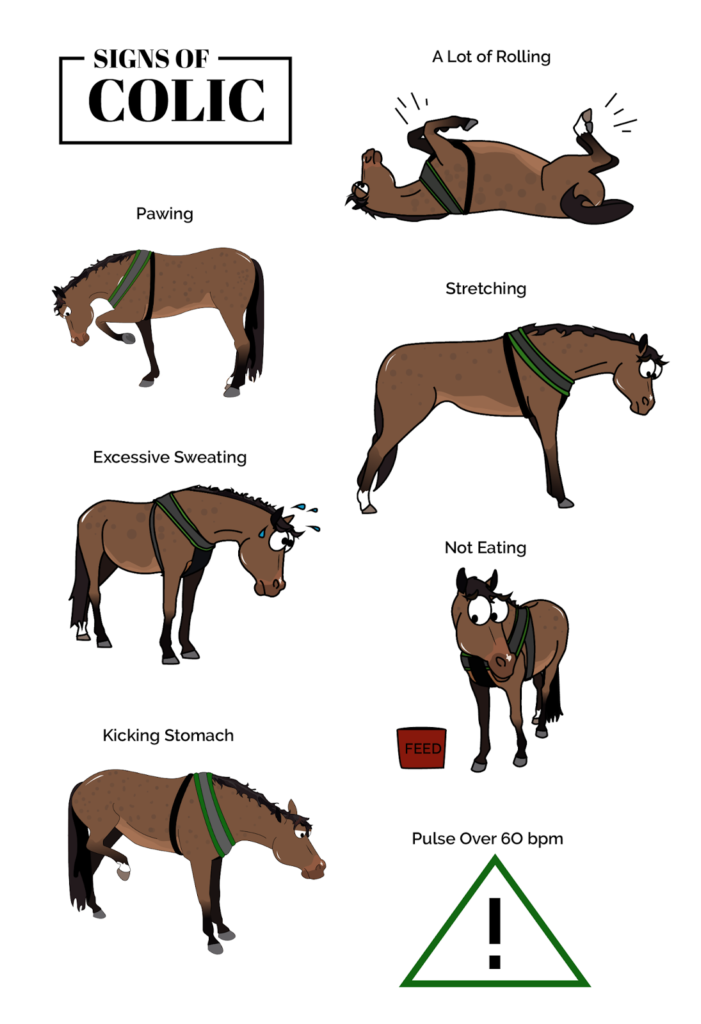

Colic is a common problem in horses with 4-10 colic episodes per 100 horses each year. Most cases can be treated successfully medically, leaving just 2-4% of cases where the horse either needs to have surgery or be put to sleep. Medical causes of colic include gas accumulation, sometime when the fresh grass comes through, sand accumulation and colon displacements. Investigations include rectal examination, abdominal ultrasound scan blood analysis and collecting a fluid sample from inside the abdomen. Food is often withheld, but usually drinking water is allowed. Painkillers and muscle relaxants will often be given. Horses may be drenched with laxatives, electrolytes and psyllium to help shift sand. If dehydrated intra-venous fluids may be given at the clinic.

Sand Colic

A Gastrointestinal sand accumulation is a common cause of equine colic. There are many factors that contribute toward ingestion of sand in horses, including the geographical location (i.e. PERTH), feeding and husbandry, stocking density and overgrazing, as well as abnormal behaviours such as frank sand ingestion in some animals. Sand is ingested and is thought to accumulate in the large colon due to a large diameter and reduced flow rate, allowing for sand to settle out of ingested feed. The most common presenting signs of sand enteropathy include scoury diarrhoea, and colic; some horses requiring surgical intervention due to a complete obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract resulting in unrelenting colic pain.

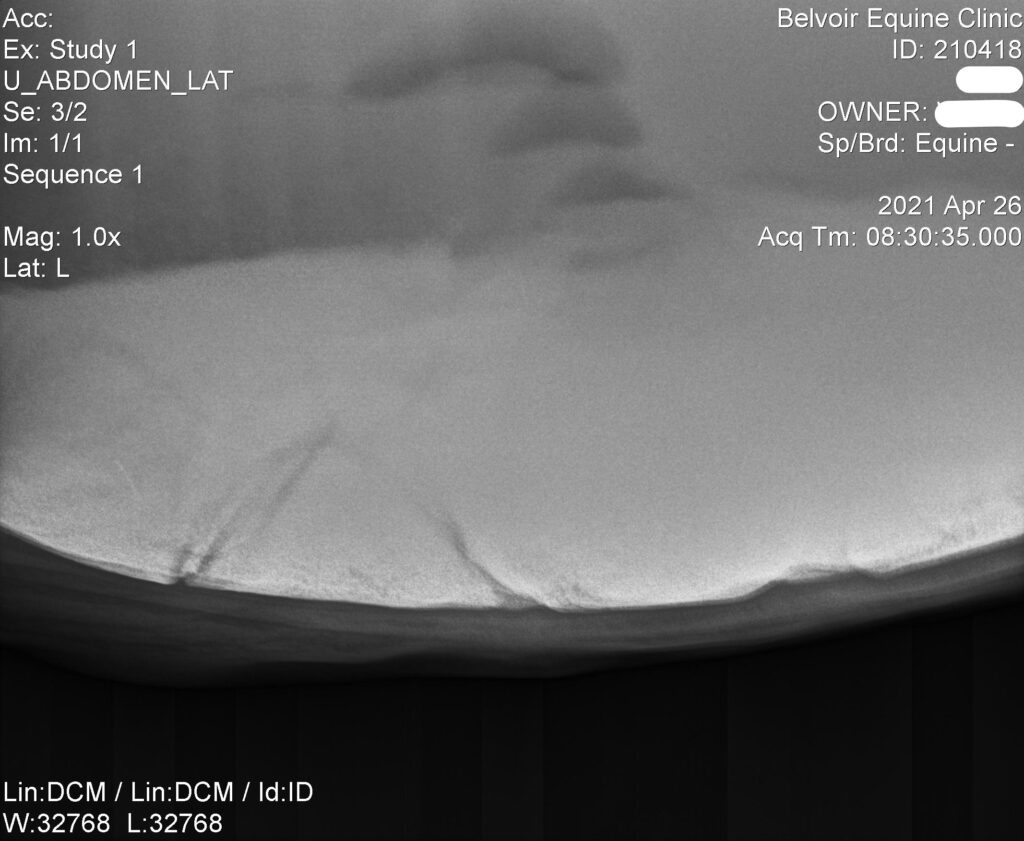

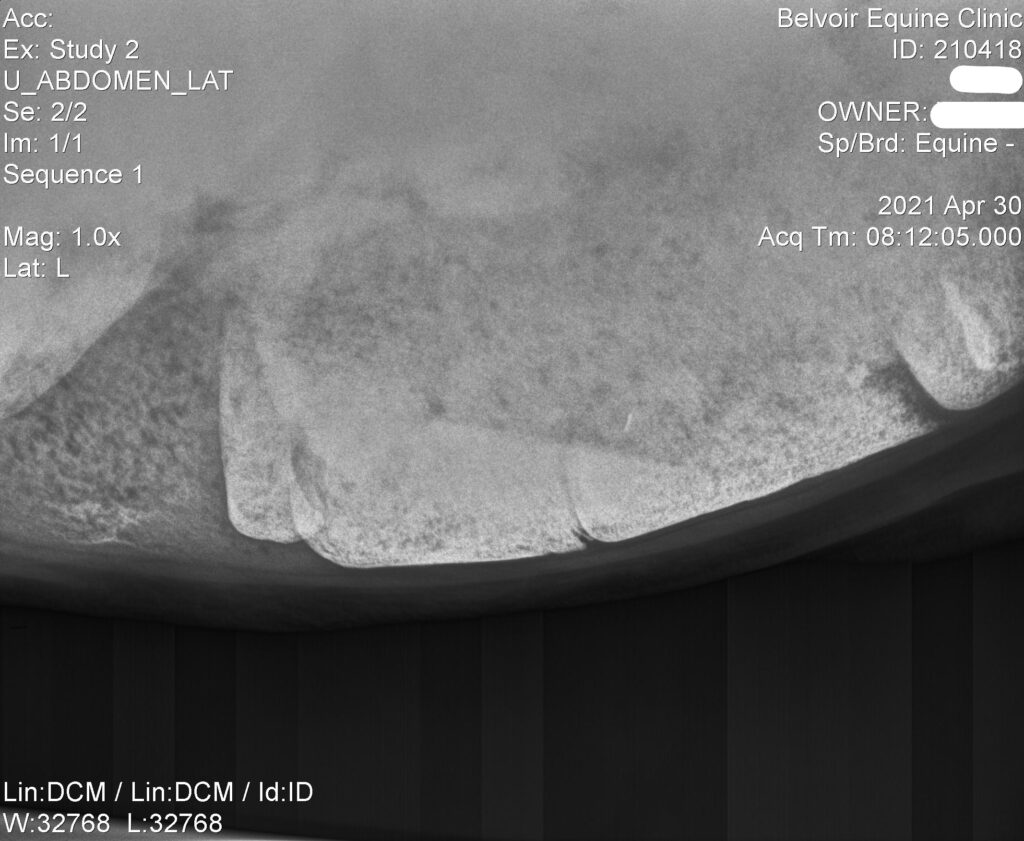

At Belvoir, sand enteropathy is on the differential diagnosis list for any horse presenting to the hospital for colic signs. On some occasions, it is possible to hear the characteristic sound relating to movement of sand when auscultating the abdomen of the horse; however, this is not always the case as it requires intestinal motility and contact with the affected region of the colon with the abdominal wall. In other horses, it may be possible to palpate a sand impaction on transrectal palpation as part of a diagnostic workup, but this is not always possible and depends on the location and weight of the accumulation which may cause the colon to drop out of reach of the examiner. Some case reports have quantified the amount of sand removed from the colon during colic surgery, and weight of retrieved sand has reached 70kg in some horses! The most reliable means of diagnosing sand enteropathy in the horse is by acquiring abdominal radiographs, which are performed in the standing horse very easily in the hospital setting. This is an objective means of evaluation, Once diagnosis of sand enteropathy is confirmed, intensive treatment can commence when the clinician is satisfied with adequate volume of defecation and resolution of colic signs.

Treatment is generally undertaken over 5-7 days, and involves daily administration of Epsom Salts (magnesium sulphate) with psyllium husk at a rate of 1g/kg body weight. This equates to a large quantity – 500g for a 500kg horse. The treatments are very unpalatable to the horse, which when combined with the quantity required for treatment, means that daily tubing is well tolerated by most horses, and is an efficacious treatment method. Follow up radiographs are usually taken around day 5 to see whether or not treatment needs to continue past this milestone, as in some horses the burden has cleared by this time.

Although a very common cause of colic in horses in Perth, sand enteropathy is not as innocuous as it may seem, and can cause severe clinical disease requiring surgical intervention in some animals, or even death should rupture of the colon occur. If you have questions about sand enteropathy, management and prevention, please don’t hesitate to get in touch!

Surgical Colic

Until 60 years ago the prognosis for colic surgery was considered to be hopeless, but advances in surgical technique, anaesthesia and post operative intensive care mean that 70-80% of horses undergoing colic surgery now survive.

In cases which require surgery there is usually a blockage, twist or displacement in the intestines which prevents the normal passage of food material. This causes significant pain, and may mean that a section of the intestine is starved of oxygen and dies. These patients are often in a lot of pain, rolling and kicking uncontrollably. They will also have a fast heart rate, quiet gut sounds and abnormal findings on a rectal exam. In order to determine the nature of the problem, a vet might also wish to perform other investigations including an ultrasound scan of the intestines, passing a tube down the nose into the stomach to release trapped fluid, running blood tests and collecting a sample of fluid from the abdomen.

Once a twist, blockage or displacement has been confirmed, and the fact that the problem is not going to be able to be treated medically has been established, the decision whether to operate on the horse or to euthanase it must be made. This is not an easy decision for an emotional and anxious owner to make, but given that any delay would worsen the prognosis, it must be made quickly. Many factors must be taken into account including how sick the patient is, how old they are, their use or purpose, their value – both financial and emotional, and also the veterinary fees that will be incurred. It is not uncommon for the invoice for a horse that has colic surgery and post-operative intensive care to be in the region of $15,000. It would of course be sensible for horse owners to decide in advance what they would do if they were ever in that situation.

Once the decision to operate has been made, the patient must be transported to a practice where colic surgery is undertaken. This will usually be a referral hospital or large practice where specialist equine surgeons, anaesthetists, intensive care medics and nurses are ready to receive them. Without delay and at any time of the day or night, the horse will be given a general anaesthetic for surgery to begin. The horse is walked into a padded room where the anaesthetic drugs are given through a catheter pre-placed in the jugular vein. These medicines cause the horse to lose consciousness and fall to the ground in a controlled manner. Once unconscious, hobbles are placed around the horse’s pasterns and it is lifted with a mechanical hoist, moved using an overhead gantry and positioned on its back on a padded surgery table.

The surgical team consists of a minimum of 4 people:

1) A lead surgeon, who is always a vet and in most cases will have undertaken further post graduate training to become a recognised specialist in equine surgery.

2) An anaesthetist who may be a vet or an experienced nurse. They are responsible for maintaining the horse at the correct depth of anaesthetic – not so light that they are at risk of starting to wake up or feeling pain, and not so deep that the health of the vital organs might be compromised.

3) A surgical assistant who might be another vet, a nurse or often a veterinary student.

4) A theatre nurse who has responsibility for theatre hygiene and safety protocols, for horse, humans and equipment. Everyone wears hats, face masks and scrub suits, and the surgeon and his assistant wear sterile gowns and gloves, having already scrubbed their arms and hands.

The horse is kept asleep by inhaling anaesthetic gases which are delivered by a large ventilator through a long tube placed through its mouth and into its trachea. Horses requiring colic surgery are often dehydrated, so this is corrected by rapid administration of an electrolyte drip. Like in human operating theatres there are many machines that go ‘ping’. The anaesthetist will use electrical aids to monitor the horse’s heart rate & rhythm, blood pressure, blood oxygen saturation and the concentration of gases breathed in and out by the patient (oxygen and the anaesthetic agent in, carbon dioxide out). In addition to bright lights the surgeons have a variety of equipment to assist them including cameras, machines to coagulate bleeding blood vessels and surgical staplers.

The hair is removed from the horse’s abdomen using clippers and the skin is scrubbed to remove dirt and micro-organisms. An incision is made into the underneath of the abdomen starting at the umbilicus and continuing for 20-30cm towards the sternum. From here the entire abdomen can be explored. Twists can be corrected, blockages cleared and displacements replaced.

One of the most common problems which results in horses requiring colic surgery is a pedunculated lipoma. This is a fatty lump often the size of an orange which hangs from a thin piece of tissue – like a conker hanging from a string. This lipoma can exist for many months without causing a problem, but on a particular day, it might move around and twist itself around a piece of the intestine. The string can then get rapidly tighter trapping the piece of intestine, cutting off its blood supply and causing it to die. In such a situation it is often necessary to remove the lipoma and the dead section of the intestine, then suture the healthy ends back together.

In about 5% horses it is not possible to correct their problem, and these patients are put to sleep on the operating table. However the majority of patients have their abdominal wound closed with strong sutures and are moved back into the padded room to come around from the anaesthetic. This begins one of the most risky periods for the horse. As part of the recovery process a tired and very sick animal, often weighing 500-700kg, must get itself up. Since colic surgery can be a relatively long procedure often lasting between 1.5-3 hours, the horse’s muscle can be weak, and the horse is often scared and uncoordinated. The veterinary team will maintain a dark quiet environment and will assist the horse to stand using ropes attached to the head and tail, but severe injuries can still happen.

Even after re-gaining consciousness and walking to a stable, the horse is still not out of the woods. Their care will then be continued by a vet who specialises in medicine and intensive care and by dedicated nursing staff. The horse will receive an intra-venous drip to maintain hydration, antibiotics and painkillers. Their heart rate, gum colour, temperature and intestinal sounds will be monitored every 2-3 hours, and horses will have regular blood tests. The biggest problem at this stage is that following the trauma that the intestines have suffered, they stop working and fluid backs up inside them like in a blocked drainpipe. To counteract this, the trapped fluid is syphoned off from the stomach using a long tube passed down the nose, and medicines to stimulate the intestines to contract are given.

If further problems are going to occur they usually do so in the first 3 days after surgery, and unfortunately about 20% of horses which recover from the general anaesthetic die or are euthanased during this time. Happily however a good number of horses do survive to go home and after approximately 3 months stable rest to allow their wounds to fully heal, go on to have full and active lives. Healthy horse, happy owner, satisfied vet team.